The Sustainable Message: How Great Art Transcends Its Historical Moment

In the previous article, my colleagues discussed my approach to viewing art—specifically, how I look for what I’ve coined among my peers as the “sustainable message” embedded in artistic works. This perspective has fundamentally shaped how I experience art, choose artists to partner with, select pieces into my space, and make recommendations to collectors.

Most of us are drawn to art by our first impressions—vibrant colors, striking compositions, investment potential, or that indescribable quality that makes us stop and look—but I believe there's a deeper question worth asking. Beyond the initial attraction lies a more meaningful question: What does this piece communicate about our relationship with the world around us?

This question isn’t about limiting artistic appreciation; rather, it’s about expanding it. When we look for environmental consciousness, social responsibility, or messages of stewardship within art, we discover layers of meaning that pure aesthetic judgment might overlook. We begin to see how artists wrestle with the pressing issues of our time, their work inspiring us toward more thoughtful living. Art has the power to shift our perspective, to open our eyes to unseen connections, and to awaken a sense of responsibility or wonder—to pay closer attention to our surroundings, to engage with others more compassionately, and to consider the broader impact of our choices.

In this article, I want to explore exactly what this approach means in practice—how the “sustainable message” influences my art selection process, and why I believe this framework should become a fundamental consideration for anyone serious about collecting or simply appreciating art in our current era. Art that endures possesses a paradoxical quality—it addresses the specific circumstances of its time but also speaks to something universal in human experience. Such work represents the rare achievement of artists who harness their historical moment not as a constraint, but as a catalyst for timeless expression.

The Paradox of Historical Specificity and Universal Appeal

The most enduring artworks are deeply rooted in their historical context while simultaneously transcending it. Love, suffering, beauty, mortality, and the human condition are subjects that transcend cultural and temporal boundaries, yet they must be expressed through the specific visual, cultural, and technological vocabulary available to each artist’s era. Consider Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665). The painting emerges from the specific context of the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age, a period marked by economic prosperity, a fascination with light and optics, intimate domestic settings, and evolving social dynamics. Yet the work’s power lies not in its historical documentation but in its capture of something eternal—the play of light on human features, the mystery of a glance, the tension between intimacy and distance. The complex emotions Vermeer captured in a single frame proved so compelling that, more than three centuries later, they inspired Girl with a Pearl Earring, a bestselling novel by Tracy Chevalier that sold over five million copies worldwide. The story was later adapted into a full-length film, reimagining the painting’s mysterious origins with a young Scarlett Johansson playing the key role.

Théodore Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa (1819) powerfully captures the paradox at the heart of Romanticism—deep emotion grounded in real events. Based on the 1816 wreck of a French naval frigate, the painting goes beyond its specific colonial and maritime context to explore universal themes of suffering, survival, and hope. While many Romantic artists used history to glorify national pride, Géricault used it as a platform for critique. The artist presents a chaotic scene that confronts the brutal reality of disaster. The painting’s lasting impact comes not from its historical accuracy, but from its raw depiction of ordinary people facing extraordinary challenges. This makes it just as relevant to modern audiences dealing with their own struggles as it was to viewers in the 19th century. By weaving together themes of political corruption, colonial exploitation, and racial equality within a framework of universal human struggle, Géricault created a masterpiece that continues to resonate across cultural and temporal boundaries.

Similarly, Picasso’s revolutionary Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) was born from artistic rebellion and the influence of African art, yet it continues to speak to our modern understanding of identity’s fragmented nature and the complexity of perception. The work’s formal innovations served not merely to shock contemporary audiences but to reveal enduring truths about how we see and understand ourselves. Shocking in its time, the work not only had a profound impact on modern art but continues to challenge societal expectations. It confronts the issue of power—specifically the imbalance between men and women, where women are often reduced to objects of desire through the male gaze. Picasso’s portrayal of these women, both vulnerable and assertive, forces us to question how power shapes identities and relationships, making the painting a timeless commentary on issues that are still deeply relevant today.

Vermeer’s mastery of light is evident in the softness of the girl’s face, the subtle highlights on her lips, and the shiny pearl.

The painting touches on themes of race and colonialism. Among the survivors of the wreck were enslaved Africans, part of France’s broader colonial enterprise. Géricault’s decision to prominently feature a Black figure at the center of the composition is significant—it not only highlights the suffering of enslaved people but also subtly critiques the colonial system. The Raft of the Medusa stands as a landmark work of Romanticism.

This piece by Picasso is widely hailed as the birth of Cubism and one of the most revolutionary works in modern art. It depicts five nude female figures in a brothel, their bodies fractured into sharp angles and planes. The two figures on the right bear a striking resemblance to African masks—marked by stylized features, elongated forms, and exaggerated eyes.

The Role of Universal Themes

Art is the reflection and expression of the human condition. Our dreams, passions, struggles and joys can be expressed, realised or even purged through art. The artists who create works with sustainable messages understand this fundamental truth. They recognise that while fashions, technologies, and social structures change dramatically, the core human experiences remain remarkably consistent across centuries.

The hero’s journey, for instance, appears in artistic expressions from ancient Greek epics to contemporary cinema because it reflects something fundamental about human growth and transformation. The universal appeal of the hero’s journey lies in its portrayal of personal growth through adversity, whether expressed through Homer’s Odyssey or modern narratives like J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter.

The Visual Strength That Transcends Time

What distinguishes art with a sustainable message is its visual strength—elements that remain powerful regardless of changing aesthetic preferences. This strength typically manifests in several key areas:

Compositional Mastery: Works that endure often possess underlying structural principles that remain compelling across different artistic movements. The golden ratio, dynamic symmetries, and principles of visual balance speak to something fundamental in human perception that transcends stylistic trends. For a deeper exploration of these concepts, I recommend The Painter's Secret Geometry: A Study of Composition in Art by Charles Bouleau.

Emotional Authenticity: Genuine emotional expression, whether joy, melancholy, or contemplation, resonates across cultural boundaries. The specific cultural markers may become dated, but authentic emotion remains universally recognisable.

Technical Excellence: Masterful handling of medium—whether paint, stone, or digital media—creates a visual authority that commands respect across generations. This technical mastery serves not as an end in itself but as a vehicle for deeper expression.

Symbolic Resonance: Effective use of symbols and metaphors that tap into shared human experiences rather than temporary cultural references. Light and shadow, for instance, have carried metaphorical weight across cultures and centuries.

Benjamin’s Concept of Aura and Historical Context

Walter Benjamin’s influential essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, provides important insight into how art relates to its historical moment. The uniqueness of a work of art is inseparable from its being embedded in the fabric of tradition, Benjamin argued. Yet this embedding doesn’t limit great art—it provides the very foundation from which it can speak to future audiences.

Benjamin believed that art is always connected to a tradition—it doesn't just appear out of nowhere. But he also thought this tradition isn't fixed or frozen in time. It's alive, constantly shifting, and open to change. The best artists, he said, are the ones who know how to work with that. They understand their place in history, and they use it both as a foundation to stand on and as a launchpad to push things forward. In other words, they respect the past, but they’re not afraid to change it or challenge it.

Walter Benjamin’s Essay:

These questions around originality, context, and reproduction echo ideas explored in Walter Benjamin’s landmark essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. For those interested in a deeper understanding of how technological change reshapes our experience of art, Benjamin’s insights remain essential reading. Get the full essay here.

The Artist’s Vision: Embracing and Transcending Circumstances

Creating art with a sustainable message requires artists to maintain a dual perspective. They must be acutely aware of their cultural moment—its anxieties, innovations, and possibilities—while simultaneously possessing the vision to identify which elements of human experience will outlast temporary conditions.

This approach calls for focusing on the fundamentals rather than the superficial:

- The play of light rather than the fashion of clothing

- The expression of longing rather than its specific contemporary object

- The structure of human relationships rather than their particular social arrangements

- The gesture of hands rather than the style of gloves

- The architecture of the face rather than the makeup of the era

This is not to say that surface details should be ignored, but rather that the focus should remain on the elements that have consistently transcended time—those that speak to shared human experience across generations.

Contemporary Implications

In our digital age, the challenge of creating sustainable messages has become increasingly complex. Contemporary artists must navigate rapidly evolving technologies, global cultural exchange, and the unprecedented speed of communication. Yet the fundamental principle remains the same: the most enduring contemporary art is that which uses current tools and contexts to explore timeless themes.

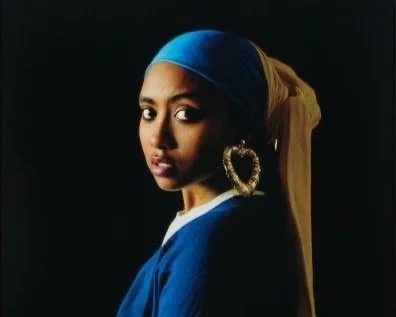

A powerful example of this shift is the rise of Black artists on the global stage, who are challenging the dominance of Eurocentric perspectives within the established art historical canon and broadening the definition of beauty beyond its traditionally narrow lens. Earlier, we touched on Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665)—a work long held as an icon of classical Western art. Building on that reference, it’s worth exploring how contemporary artists are reinterpreting such canonical works to question and expand the narratives that have historically excluded other cultural voices. One striking example is the work of Awol Erizku, who reimagines Vermeer’s portrait in his photograph Girl with a Bamboo Earring (2009). Through this piece, Erizku confronts issues of representation and identity, reframing the familiar image within the context of Black aesthetics and lived experience. His work not only challenges the authority of the Western canon but also opens up space for new voices to be seen and heard.

In Erizku’s photograph Girl with a Bamboo Earring (2009), the subject—a Black woman wearing a bamboo hoop earring—transforms Vermeer’s iconic portrait into a contemporary image rooted in Black aesthetics. The work simultaneously honors and subverts the original, employing the visual language of today to assert new narratives within the artistic tradition. In doing so, it demonstrates that art endures not merely by preserving the past, but by inviting new voices to engage with it—transforming historical icons into living, contested symbols of shared humanity. It would be compelling to see both works exhibited side by side—a dialogue across time that highlights their shared visual language and distinct cultural voices.

Street artist Banksy, for instance, uses contemporary urban settings and current political issues to explore enduring themes of power, resistance, and human dignity. While the specific references may anchor the works in a particular moment, their emotional core resonates with universal experiences of social frustration and hope. In December 2015, Banksy reimagined The Raft of the Medusa (1819) as a black stencil on a Calais wall, preserving Géricault's dramatic composition while updating its meaning. His version depicted migrants on a raft waving desperately toward a modern luxury yacht—replacing the original rescue ship with a symbol of Western indifference. The work directly referenced refugees from the nearby “Jungle” camp, many of whom were trying to cross the English Channel. Located just steps from the camp, the mural's political message was both immediate and unavoidable. In 2017, the homeowner painted over the artwork, calling it shabby—though the now-blank wall still draws curious visitors. Banksy's adaptation powerfully illustrates how classical art can be repurposed to confront urgent humanitarian crises, preserving the original's emotional weight while delivering sharp social critique.

Awol Erizku’s Girl With a Bamboo Earring nods to Vermeer while making a bold statement about beauty and culture today. Like Kerry James Marshall, Chris Ofili, and Kehinde Wiley, he highlights the lack of Black presence in art history—but instead of sticking to tradition, Erizku pushes beyond it, creating work that speaks to a wider world.

Just as Géricault transformed a 19th-century maritime disaster into a commentary on government negligence and human abandonment, Banksy uses the same compositional framework to critique contemporary European immigration policies and the abandonment of refugees seeking passage to Britain.

Conclusion: The Eternal in the Temporal

Great art is like a time machine, allowing viewers to connect across centuries through shared human experience. The most enduring works achieve a "sustainable message"—emerging from their specific historical moment yet speaking directly to every generation.

This timeless quality doesn't come from avoiding contemporary issues or appealing to the lowest common denominator. Instead, it requires artists to deeply understand both their own era and the fundamental experiences that unite all people across history: love, loss, hope, struggle, and the search for meaning. When artists succeed in this dual understanding, they create works that function simultaneously as historical documents and prophetic visions—capturing the essence of their time while revealing truths that remain relevant centuries later.

These works don't escape their historical moment but penetrate it so deeply that they illuminate the timeless human condition, making them perpetually meaningful to audiences across all eras. This represents the highest achievement of artistic vision: the transformation of the temporal into the eternal through the alchemy of authentic creative expression.

References

https://www.banksy.co.uk/index.html

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New York: Pantheon Books, 1949.

Chevalier, Tracy. Girl with a Pearl Earring. London: HarperCollins, 1999.

Elkins, James. Visual Studies: A Skeptical Introduction. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Truth and Method. 2nd ed. New York: Continuum, 1989.

Gombrich, Ernst H. The Story of Art. 16th ed. London: Phaidon Press, 1995.

Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by R. Fitzgerald. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990.

Panofsky, Erwin. Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press, 1939.

Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter Book Series. London: Bloomsbury, 1997.