The Museum of West African Art: Reclaiming Heritage and Rewriting History in Benin City

A Personal Connection

When FreshLemonWater began planning coverage of the Museum of West African Art (MOWAA) in Benin City, my father's hometown called—and I couldn't stay silent. For much of my life, Benin City has been more myth than memory—real in stories, elusive in experience.

My first reaction was scepticism: "Another beautiful dream that'll never materialise." Especially when I discovered the project was championed by outgoing Governor Godwin Obaseki. Anyone familiar with Nigerian politics knows the fate of a predecessor's flagship projects: quietly packed away with the brown boxes on moving day.

I was wrong.

Construction is actively underway on facilities designed by David Adjaye, scheduled to open November 11, 2025.¹ This project defied political odds, sustained by international stakeholders who refused to let it become another casualty of electoral change. When that realisation hit, this stopped being just another article. It became personal.

Aerial view of MOWAA construction site, Benin City. Image courtesy of the Museum of West African Art.

Growing up, my understanding of Benin City has been defined by a single violent moment—the 1897 British raid that stripped the kingdom of thousands of cultural treasures. MOWAA offers something I didn't know I'd been waiting for: a chance to see my father's homeland not through what was taken, but through what's being restored—and what's still being discovered.

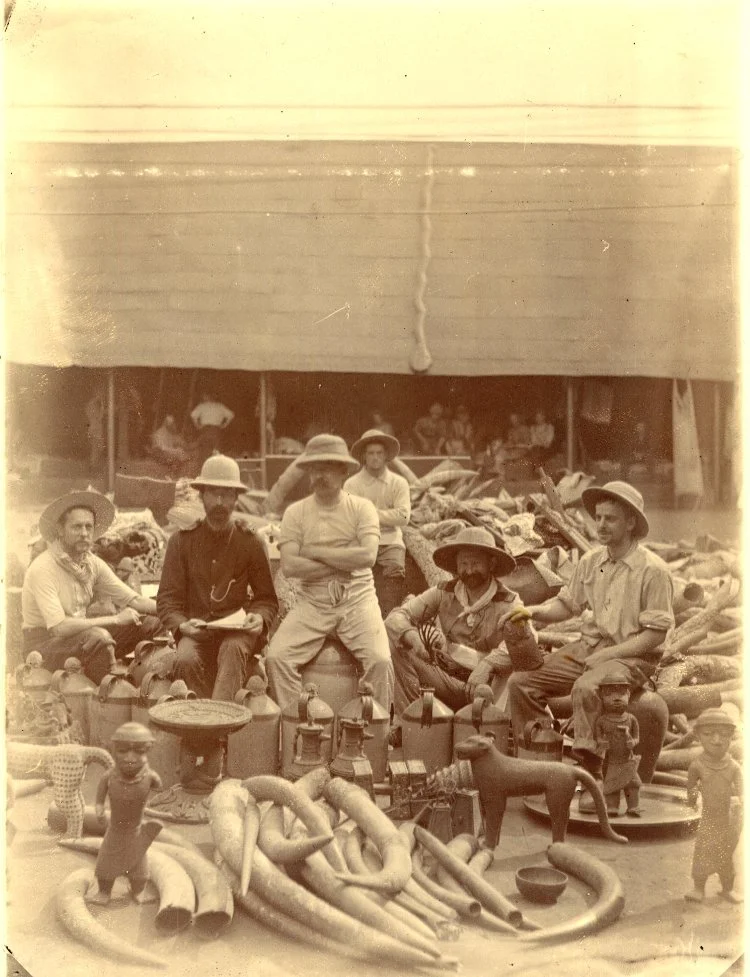

British expedition members pose with artefacts looted from The Benin Royal Palace, 1897

Courtesy of The British Museum - Af,A79.13

A Painful Provenance: The 1897 Looting and Its Enduring Legacy

In February 1897, British forces launched a punitive expedition against the Kingdom of Benin, burning the city, ransacking the royal palace, and seizing thousands of artefacts.² It was a single decisive collapse of an empire that, for approximately 700 years of its history, had not lost a war in the region—a calculated act of intimidation that sent shockwaves across West Africa, warning neighbouring kingdoms that British imperial power would tolerate no resistance to its ambitions of resource control in the region. The looting extended beyond the Benin Bronzes to encompass brass plaques, ivory carvings, coral regalia, ceremonial objects, textiles, and ritual items that embodied the kingdom's cultural memory.

These artefacts documented Benin's historiography, religious practices, diplomatic relations, and political legitimacy. Their removal constituted systematic historical erasure. Germany committed to repatriations in 2021, whilst institutions including the Smithsonian and Cambridge's Jesus College have returned specific pieces.³ Yet thousands remain scattered across Western collections—making MOWAA's mission vital in assisting to establish lost cultural links.

Building MOWAA: Vision and Location

MOWAA represents a collaborative vision between the Edo State Government and international partners including the Legacy Restoration Trust.⁵ Designed by Adjaye Associates, the project draws inspiration from Benin's ancient city layout—once defined by vast earthworks, courtyards, and shrines.¹ Planned as a cluster of museum pavilions, archives, and creative studios, MOWAA will serve as a catalyst for artistic production, research, and cultural collaboration across West Africa.

Located in the heart of Benin City, adjacent to the royal palace, the museum occupies profound historical ground. As the seat of the Benin Kingdom—whose influence once extended across present-day southern Nigeria and West Africa to present-day Ghana—the city possesses geographical, cultural, and moral authority over these artefacts. Institutions like MOWAA challenges the colonial assumption that African heritage requires European guardianship.⁶

Museum of West African Art (MOWAA), Benin City — architectural rendering by Adjaye Associates. Courtesy of Adjaye Associates

Museum of West African Art (MOWAA), Benin City — architectural rendering by Adjaye Associates. Courtesy of Adjaye Associates

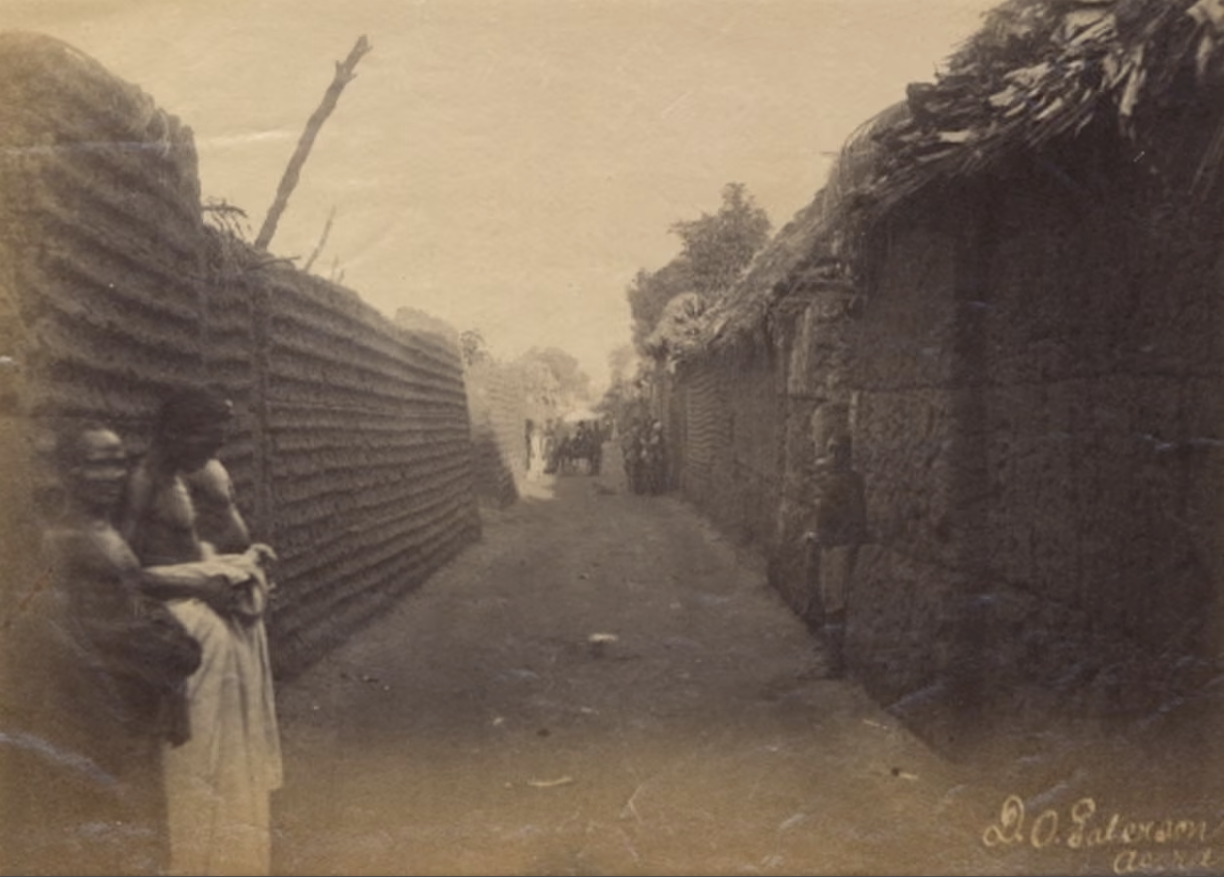

The museum’s façades feature textured surfaces and earthy tones, evoking the visual language of traditional mud walls in Benin architecture which can be seen in this photograph showing a view along a street in the royal quarter of Benin City, 1897. Courtesy of The British Museum/Trustees of the British Museum

The Museum's Mission: Beyond Display

MOWAA transcends traditional museum functions. It includes a comprehensive institute dedicated to decolonising history, conducting archaeological research across West Africa, and revealing how our ancestors created technologies that produced some of the world's most revered artworks.⁷ State-of-the-art conservation laboratories with the capacity to preserve returned artefacts whilst training Nigerian conservators in specialised techniques.

Ongoing archaeological excavations are set to illuminate deeper understanding to the indigenous craftsmanship: advanced lost-wax casting techniques, ivory carving traditions, and architectural innovations.² MOWAA collaborates with international scholars whilst prioritising local voices, oral histories, and indigenous knowledge systems.

Critically, exhibitions counter colonial representations. Rather than displaying objects as "primitive art," the museum contextualises them through display in the environment which served as the source of inspiration mostly highlighting the complex political structures, philosophical systems, and aesthetic traditions. Temporary exhibitions feature contemporary West African artists, demonstrating living cultural traditions rather than frozen history.

Local and National Impact

For Edo communities, MOWAA facilitates cultural healing, reconnecting generations with ancestral heritage. Economically, it diversifies revenue beyond oil dependency, attracting international visitors and creating employment across curatorial, conservation, hospitality, and artisan sectors. Nationally, MOWAA positions Nigeria as a leader in Africa's cultural renaissance.

Significantly, MOWAA introduces archaeological practice directly to local communities. Students are invited to witness excavations and conservation work firsthand, demystifying processes once monopolised by Western institutions.² This exposure expands young minds, sparking interest in history and archaeology amongst a generation that can now see themselves as custodians and interpreters of their own heritage. Schools incorporate museum visits and archaeological fieldwork into curricula, transforming abstract history lessons into tangible connections with ancestral achievement. For many young Edo residents, MOWAA represents the first opportunity to engage with archaeology not as distant academic practice, but as living inquiry into their own past.

Students participating in a live archaeological dig activation at MOWAA Open Day in May 2023. Image courtesy of the Museum of West African Art.

Conclusion: The Way Forward

MOWAA represents a watershed moment in cultural restitution and decolonisation. Its survival through political transition demonstrates that return is feasible and morally imperative, refuting paternalistic arguments against repatriation.⁶

International museums must accelerate returns, recognising that indefinite retention perpetuates colonial injustice. Documentation and digitisation can facilitate global access without requiring physical possession.⁴ MOWAA's model should inspire similar institutions across Africa, creating networks that share expertise and challenge Western museological dominance.

Whilst questions of custodianship between the Edo State Government and the Oba’s Palace have now been resolved—with the returning Benin Bronzes designated for housing within the new Benin Royal Museum at the palace—the wider mission of cultural stewardship continues. The Museum of West African Art (MOWAA) has since redefined its role, shifting from being the primary repository for the Bronzes to a broader institution dedicated to West African arts, heritage, and creative innovation. Its work now centres on research, conservation, education, and contemporary art practice, in collaboration with partners such as the National Commission for Museums and Monuments, the British Museum, and the German Archaeological Institute. MOWAA also leads an ongoing archaeological project on its Benin City campus, contributing new insights into the ancient kingdom’s history. It is also quite possible that the Benin Royal Museum will partner with the MOWAA Institute on future preservation and conservation initiatives, given their shared commitment to safeguarding cultural heritage. In this light, the resolution of custodianship marks not an end but an evolution: while the Benin Bronzes return to the care of the palace, MOWAA continues to grow as a dynamic cultural hub for research, exhibition, and the celebration of West African art.

The return of the Benin Bronzes transcends object transfer—it represents epistemological decolonisation, reclaiming the power to narrate African history.⁶ For those who grew up with gaps in cultural understanding, MOWAA offers profound restoration. The artistic legacy of West Africa, once scattered and silenced, now speaks powerfully from its rightful home. November 11, 2025, marks not an ending but a beginning—the start of a chapter in which we honour our past whilst building our future, and the narrative of African art is finally, rightfully, ours to tell.

References

¹ Adjaye Associates (2021) 'Edo Museum of West African Art', Adjaye Associates. Available at: https://www.adjaye.com/work/edo-museum-of-west-african-art/ [Accessed 3 November 2025]

² Cambridge University Press (2025) 'MOWAA Archaeology Project: enhancing understanding of Benin City's historic urban development and heritage through pre-construction archaeology', Cambridge University Press, 30 October. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org [Accessed 3 November 2025]

³ The Smithsonian Institution (2022) 'Smithsonian Returns 29 Benin Bronzes to Nigeria', Smithsonian Newsdesk, 11 October.

⁴ Digital Benin (2023) 'Digital Benin', Digital Benin. Available at: https://digitalbenin.org/ [Accessed 3 November 2025]

⁵ Legacy Restoration Trust (2020) 'The Legacy Restoration Trust, Nigeria, the British Museum and Adjaye Associates announce details of major archaeology project on the site of a new museum in Benin City’. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/EMOWAA-Project_release_November_2020.docx [Accessed 3 November 2025]

⁶ Sarr, F. and Savoy, B. (2018) The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics. Paris: Université Paris Nanterre.

⁷ Museum of West African Art (2024) 'About MOWAA', MOWAA. Available at: https://wearemowaa.org/ [Accessed 3 November 2025]